By Richard LeComte

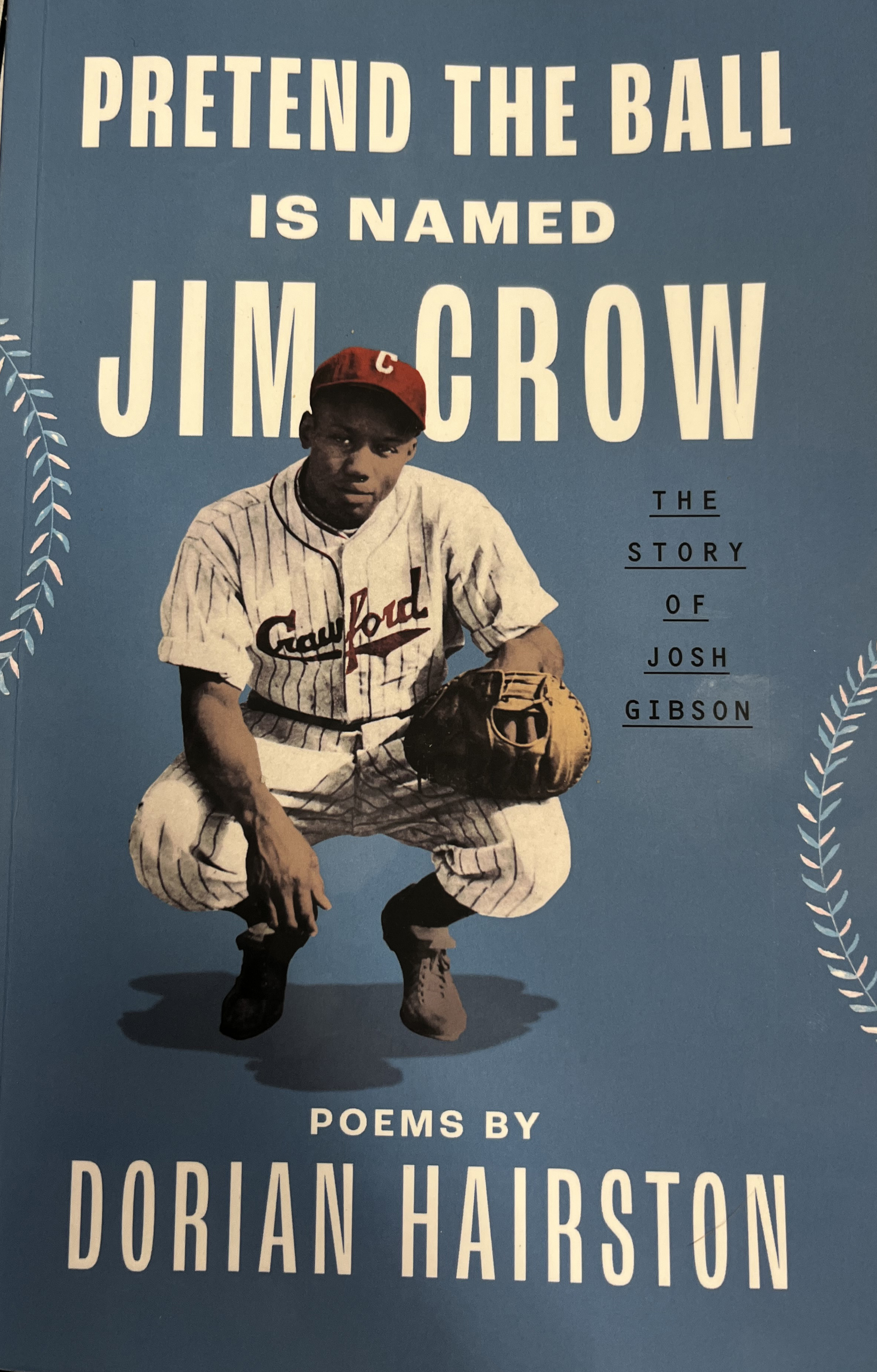

LEXINGTON, Ky. -- For baseball fans, the game can be poetry in motion: Athletes swing, catch, run, slide and throw with both power and grace. Thus it’s natural that Dorian Hairston, a former University of Kentucky baseball player, English major and writer, would use poetry to chronicle the life of one of the sport’s greatest players.

In the book, “Pretend the Ball is Named Jim Crow,” Hairston collects a series of provocative poems about Josh Gibson (1911-1947), the legendary Negro Leagues player who hit more than 800 home runs and was compared favorably to Babe Ruth. Because of segregation, Gibson never got to play in the majors, and he died just before Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers. Hairston has been interested in Gibson since Hairston’s high school days, when he played baseball at Tates Creek High School in Lexington. He focused on Gibson for a school writing assignment and became fascinated by his life and legacy.

baseball at Tates Creek High School in Lexington. He focused on Gibson for a school writing assignment and became fascinated by his life and legacy.

"Gibson met his wife when he was 17 years old, and by 20, he was a widower with two children,” said Hairston, who is studying in UK’s creative writing MFA program. “I'm reading after I had just turned 18 the second semester of my senior year. And I thought, ‘What would I do if I was experiencing this and also trying to play baseball?’ You’ve got two children. You've got to bury your wife. You're living in a segregated United States. By no stretch of the imagination am I trying to say that the United States in 2024 is perfect, but it looks different for Josh than it does for me, even though we're both black men in this space. How do you navigate all of that on top of the fact that somebody's telling you where to sit on a bus?”

The book, published in January by the University Press of Kentucky, contains 45 poems divided into different "innings,” or chapters. Each poem is in the voice of Gibson, a family member or one of his contemporaries. Hairston writes frequently of both the respect his peers felt for Gibson, Gibson’s prowess with a baseball bat and Gibson's ongoing frustration with Jim Crow. One example occurs in the poem “Pregame Cut (Josh Gibson)”:

“I wish my hair grew the speed

of my bat through the zone

and make it so I need to take a trip

to my barber every morning.

“It's like when them clippers first click,

buzz their way through to a new man,

we can laugh away the big boss,

the policeman that said we too dark

to be anywhere, our woman at home waiting

inside the front door, hip cocked

to one side, 'tude the shape

of an arm holding up a child,

and our other woman cross town

who makes us forget, all at the same time.”

Hairston traces both his interest in baseball and in poetry to his school days. His parents encouraged him to sample a variety of activities, and he lived near Lexington ballfields.

"My parents when I was growing up said, 'You're going to try everything.’ I grew up in Lexington, born and raised. My parents still live in the house that they built when I was 2 years old. Now my wife and I live about three miles from there, so I'm still in the same area.

“There's a baseball field maybe a quarter mile away from the house. I could hear the games if I wasn't playing in them. I could hear them from my bedroom. I tried everything, but baseball was just the one that not only I was good at but also had the most fun doing.”

Also at Tates Creek, Hairston encountered UK English Department faculty member Frank X Walker, who praised his work at a school poetry reading. Hairston was taking an independent study class with Phyllis Schlich, a creative writing teacher. He decided to write a series of poems reminiscent of Walker’s “Isaac Murphy: I Dedicate This Ride,” a book of poems about a Black jockey.

“I started to work with the idea of writing about Jackie Robinson, and my teacher told me, ‘I think you can do better than this; I think you need to find somebody else that people don't know as much about,’” he said. “I started doing some research. Who were some of the best Negro League Baseball players who ever existed? Then I came across this guy by the name of Josh Gibson, and I was like, man, I've never heard this name before. And then I start looking into him and I'm like, man this guy, he's a bad dude.”

Thus, Hairston graduated from high school and entered UK with the goal of playing baseball and working on a writing project. On the team, he played right field and DH and made three all-SEC academic honor rolls. In the classroom, he started out studying Integrated Strategic Communications, but with the help of Walker he switched to English.

“I emailed Walker and I said, ‘Hey, we met at Tates Creek High School. You said you liked my poetry,” Hairston said. “He did say it in front of the whole school. I asked if there was a time we could meet, because I had some questions. He responded ‘yes.’ I came to his office hours and said, ‘I don't know what I want to major in. Can you help me out?’ And he said, 'Why don't you just switch to English?’”

While an undergrad, Hairston published poetry in the journal Shale. He graduated from UK in 2016 and was one of the first students in the University’s MFA creative writing program. He also holds a Master of Arts in Teaching degree from the University of Cumberlands in secondary English education. Now married with two children, he works as a behavior coach at a Lexington elementary school. He also found time to assemble the poems he had written about and in the voice of Josh Gibson, and the University Press of Kentucky published them under the aegis of Patrick O’Dowd, the former acquisitions editor.

"This was pre-COVID,” Hairston said. “I was out at Al's Bar reading for a poetry reading. I took any and every opportunity to read my poetry in public. Patrick had been in the audience one night, and he heard my poems about Gibson. He said he thought I might have a book on my hands. ‘Whenever you're finished, ‘Let's talk.’”

One of Hairston’s friends, Yvonne Johnson, published her own book of poetry -- “I am Woman” -- and challenged Hairston to get his own poetry published within a year. He submitted his own manuscript in about three months, and the results were published in January.

As part of his writing, Hairston has looked deeply into the history of the Negro Leagues, especially the Black managers and owners who contributed to communities. When Major League Baseball integrated, the owners and general managers “cherry-picked” the stars of the Negro Leagues, but the teams themselves had been solid institutions. With integration, they eventually disappeared.

“I ask the question in the book, and I oftentimes find myself asking this question outside of the book: ‘Did we get integration right?’ And I think the short answer is no, we didn't. We could have done better. How do we make sure that an institution that was providing legitimate employment for Black baseball players and staff would be preserved? The owners were pumping money into other Black institutions inside of the cities to make sure that folks are taken care of. When we integrate, what happens to those institutions?”

Hairston said he feels a lot of anger at what he’s found in his research on baseball and Jim Crow, and the way he vents that rage is through his writing. But in the poems in “Pretend the Ball” also express Hairston’s -- and Gibson’s -- love for a game that has its triumphs as well as tragedies.

"I tried to communicate to my reader that, yeah, some of this stuff is really hard," Hairston said. “But if we just focus on how grotesque the history is, we miss the point. The point is how resilient folks are capable of being and how resilient we have been. What I try to do in my poetry is to point out that, some of this stuff is awful, but we're also capable of some really phenomenal things.”