For 25 years, Dr. Virginia G. Carter was one of the most influential figures in the cultural and intellectual life of Kentucky through her leadership of the Kentucky Humanities Council. Founded in 1972, Kentucky Humanities is an independent, nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

For 25 years, Dr. Virginia G. Carter was one of the most influential figures in the cultural and intellectual life of Kentucky through her leadership of the Kentucky Humanities Council. Founded in 1972, Kentucky Humanities is an independent, nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

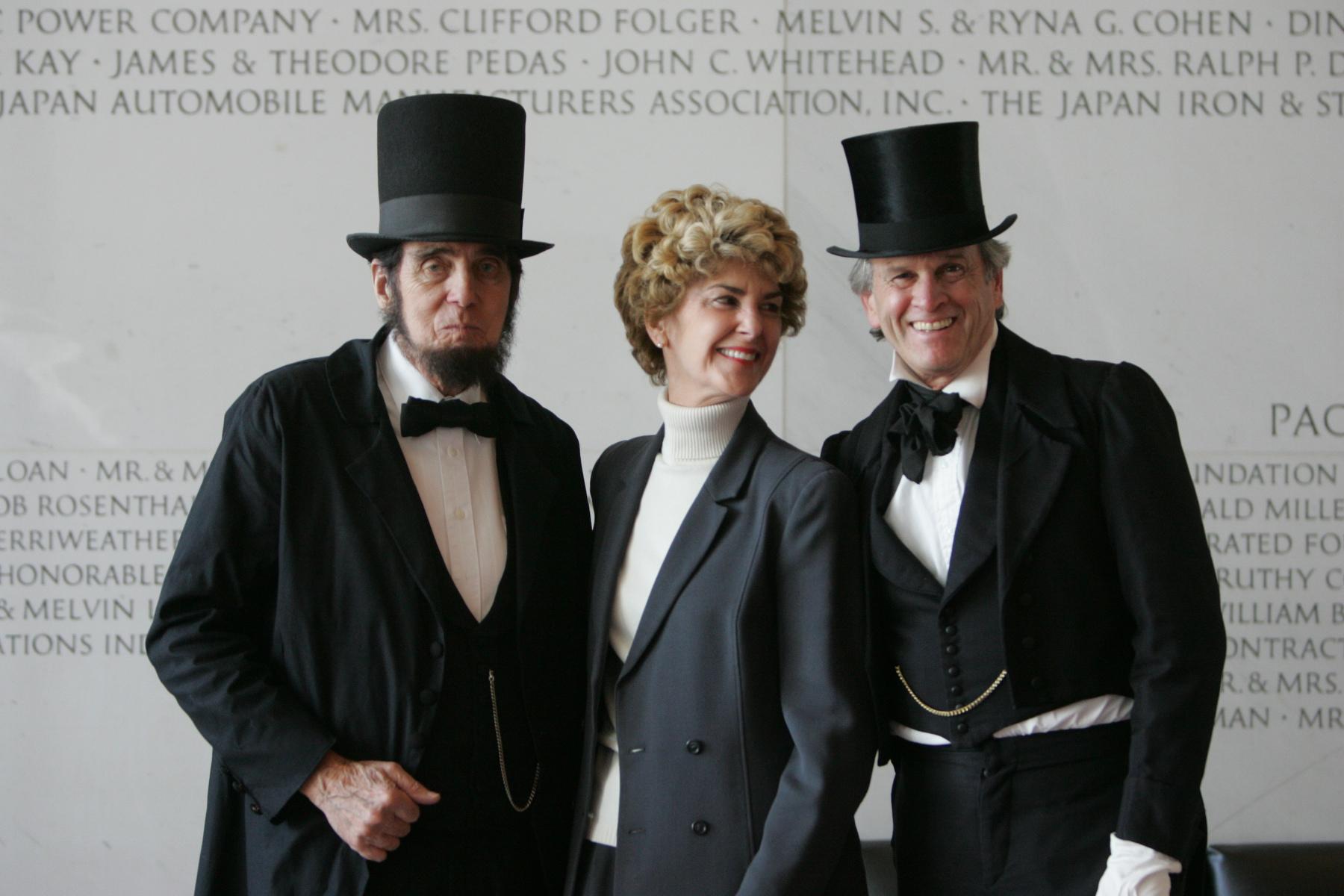

Dr. Carter transformed the organization from a grant-making body to a provider of humanities programs throughout the state. She established the Kentucky Chautauqua program, which recreates historical personalities using actors, and her production of Our Lincoln was performed nationally for the bicentennial of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth near Hodgenville in 1809.

She holds three degrees from UK, including two from the Anthropology Department, where she was the first woman to complete a doctorate in 1988, and she had a lot to say about how the department prepared her for success.

What was your childhood like and what brought you to UK?

I was born in pre-shopping mall Lexington, when our neighbors kept cows, goats and chickens. I attended school when integration was introduced, polio was a major threat and farming was a major occupation. I spent a lot of time climbing trees and catching snakes in creeks and streams. For my mother, everything was an opportunity for a science lesson: chicken for dinner meant learning about the valves of the (chicken) heart, a hike in the woods always included biological and geological classificatory systems — fossils, trees, ferns, liverworts, mushrooms, insects, reptiles, birds and the occasional stone artifact. I also spent a great deal of time drawing and painting and managed to take piano lessons for 13 years.

Too independent to enjoy the regulations of high school, I left after the first semester of my senior year and enrolled at UK. I took classes in everything except math — French and Spanish, geology, biology, art history, studio art, and one very important class in introductory anthropology. That’s when I learned about Mary and Louis Leakey’s work in Olduvai Gorge and vowed to go there one day.

As was too common in the late 1960s, I married and accompanied my then husband as he pursued his graduate education and early employment. Consequently, I enrolled in language classes at Purdue, then at LSU I earned my B.A. with majors in art, language and natural sciences.

Your first degree from UK was an M.A. in Art History in 1972. What was your path from art history to anthropology?

I lacked the confidence that I would be employable with a degree in studio art, and since I was a reasonably good writer with a broad interest in the history and culture of the makers of art, I turned to art history. I was asked to join the art department faculty at the University of Northern Iowa. There, I continued to create art and wrote reviews of exhibits for the local newspaper. UNI treated me very well and gave me a year off to go back to school. I had argued and they accepted that to qualify for tenure I could get another master’s degree — this time in anthropology — in lieu of a Ph.D. At the time, there were few graduate programs that offered art history programs in Native American, South American or non-European art. I applied for and was accepted to the graduate program at UK with a Museum of Anthropology assistantship. Happily, my art background was a plus: I illustrated artifacts for faculty publications, installed exhibits, and learned to conserve and research collections held by the department.

Which professors stand out in your memory as being important mentors?

First and foremost was Phillip Drucker, who oversaw my master’s degree studies. Professor Drucker presented me with the challenge of combining my background in art and art history with archaeological research and linguistic/artistic taxonomy to investigate the unique and little researched carved stelae of Izapa, a site in Chiapas, Mexico. He encouraged me to develop the multidisciplinary approach I later applied to my dissertation, an interpretation of artistic style and cultural meaning by “translating” visual images when no dates or writing were present. This was just the kind of synthetic approach I had been missing in art history and that led me to anthropology.

It was clear by then that I would pursue a Ph.D. in anthropology at UK. My major professor was Kenneth G. Hirth, who was conducting large research projects in Honduras and Central Mexico. Dr. Hirth asked me to contribute to his research of Xochicalco, Morelos with an iconographic analysis of carved monuments as expressions of power and politics. Although I visited the archaeological sites, happily no one gave me a trowel.

It was clear by then that I would pursue a Ph.D. in anthropology at UK. My major professor was Kenneth G. Hirth, who was conducting large research projects in Honduras and Central Mexico. Dr. Hirth asked me to contribute to his research of Xochicalco, Morelos with an iconographic analysis of carved monuments as expressions of power and politics. Although I visited the archaeological sites, happily no one gave me a trowel.

Thanks, in part, to my assistantships with the Museum of Anthropology, I also became involved with physical anthropology. David Wolf taught me soft tissue reconstruction of the faces of unidentified homicide victims. When he became Kentucky’s forensic anthropologist, I assisted in analyzing and identifying skeletal human remains at the state laboratory. With George Milner, a physical and biological anthropologist who succeeded Lathel Duffield as director the museum, I assisted in analyzing the skeletal population recovered from a salvage archaeological excavation in Illinois. Additionally, I participated in grant-supported research into the thousands of skeletal remains from the University of Kentucky’s New Deal excavations and created a traveling exhibit about that era.

Throughout these years I continued to employ my skills as an art historian and illustrator. In addition to providing renderings of the carvings and monuments in my own research, I was assigned by the Museum of Anthropology to UK’s Art Museum to create an educational program for schools in association with the Armand Hammer Exhibit. I created a coloring book about Kentucky’s first people for schoolchildren visiting the UK Museum of Anthropology, and I continued to provide illustrations for faculty research.

I still imagined that my future would include museums. But in January 1988, I applied for a rare opening with the Kentucky Humanities Council Inc. (now named Kentucky Humanities), which had funded educational programs in Kentucky archaeology, including grants I had helped author. In 1989, I became the executive director and remained in that position for nearly 25 years.

How did your anthropology background inform your leadership at Kentucky Humanities?

From a purely practical point of view, I can’t imagine a better preparation than anthropology for serving the educational needs of Kentucky communities. In the anthropology department, we worked as teams, not as individuals, as was my previous academic experience. We sought the advice of colleagues and openly shared our research. We were constantly submitting grant proposals too. That skill was invaluable as I raised funds for the work of Kentucky Humanities.

More broadly, the holistic approach of anthropology and cross-cultural training allowed me to better understand not just the cultural history of Kentucky writ large but to communicate with Kentuckians from communities large and very small about their values, issues, and beliefs, and to find ways to allow people to share and take pride in their place in their history and culture. From this perspective, community leaders contributed equally with scholars to our work. Informed by my studies in anthropology, Kentucky Humanities became a far more holistic, multidisciplinary organization, expanding its educational role to people across the Commonwealth. I found ways to work with the Kentucky Arts Council, the Kentucky Heritage Council, the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, the Kentucky Historical Society, and a multitude of cultural organizations to more fully tell Kentucky’s stories.

Kentucky Humanities is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the beginning of my tenure as director of Kentucky Humanities, there was a federal mandate to exclude programs that focused on art, the purview of the National Endowment for the Arts, which supported the Kentucky Arts Council. Throughout my career, I found ways to fully employ the arts to tell Kentucky’s stories. Believing as always that all arts, especially music and theater, could not be separated from the humanities, I combined both in a national celebration of the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In partnership with UK’s Opera Theatre, Our Lincoln, Kentucky’s Gift to the Nation was a musical, theatrical, historical extravaganza involving a cast of nearly 400.

Kentucky Humanities is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the beginning of my tenure as director of Kentucky Humanities, there was a federal mandate to exclude programs that focused on art, the purview of the National Endowment for the Arts, which supported the Kentucky Arts Council. Throughout my career, I found ways to fully employ the arts to tell Kentucky’s stories. Believing as always that all arts, especially music and theater, could not be separated from the humanities, I combined both in a national celebration of the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In partnership with UK’s Opera Theatre, Our Lincoln, Kentucky’s Gift to the Nation was a musical, theatrical, historical extravaganza involving a cast of nearly 400.

I took only one graduate course in applied anthropology. I became familiar with the concept of “change agent.” By the time I retired as director of Kentucky Humanities, it occurred to me that I had spent 25 years in that capacity. Our mission was to build civic engagement and stronger communities based on respect for all cultural traditions. When we were successful, Kentucky Humanities was applying anthropology at its best.

You describe yourself as a change agent at Kentucky Humanities. Did you find that your anthropology background provided a different sort of leadership training than, for example, an MBA?

Absolutely. Because I had to learn budgets, finance, and all the rest, but that was the easy part. The more difficult part was threading my way through all the competing interests. And I did a lot of lobbying too on behalf of humanities. I spent a good bit of time in Washington understanding the culture of The Hill and how to talk to representatives and their staff. A lot of people just dismiss their staff, but they’re the most important people. And how to understand that it’s education. It’s not going in like a lawyer and making your case. It’s relationship building and education. That’s what makes for success.

Anthropology is all about teams. It’s all about working with your fellow students and your professors. I went to college for 18 years because I loved school. School was what I did. Only anthropology had this core value of sharing what you were studying with everyone else. It was assumed that everyone had something to contribute. To me, that was just an eye opener. That was the thing that just absolutely made say this is where I belong. That sense of openness and teamwork informed everything I did, not just as a student but in my future career.